I was running errands this morning and listening to The Stranger (as one does) and as I wound through Charlottesville, I realized that the main characters inmy favorite song on the album, “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant” were married fifty years ago this month.

If you’re unfamiliar with the song, it’s seven minutes long and is a suite of sorts with a ballad at its center about two characters named Brenda and Eddie, who were the couple in high school, married at the end of July 1975, but the marriage crashed and burned quickly and they went their separate ways, though they remained friends. The premise of the song’s framing device is that Brenda and Eddie are meeting one another for dinner at an Italian restaurant, perhaps for the first time in years. While the “Ballad of Brenda and Eddie” section of the song is narrated in the third person, Eddie narrates the rest of the song, giving us one side of his conversation with Brenda (“Got a new wife, got a new life, and the family is fine”). As bittersweet as the song can be, it ends on a comfortable, warm tone with a return to a wine list from the opening (“bottle of red, bottle of white …”) and the sense that though the marriage never worked out, the friendship endures.

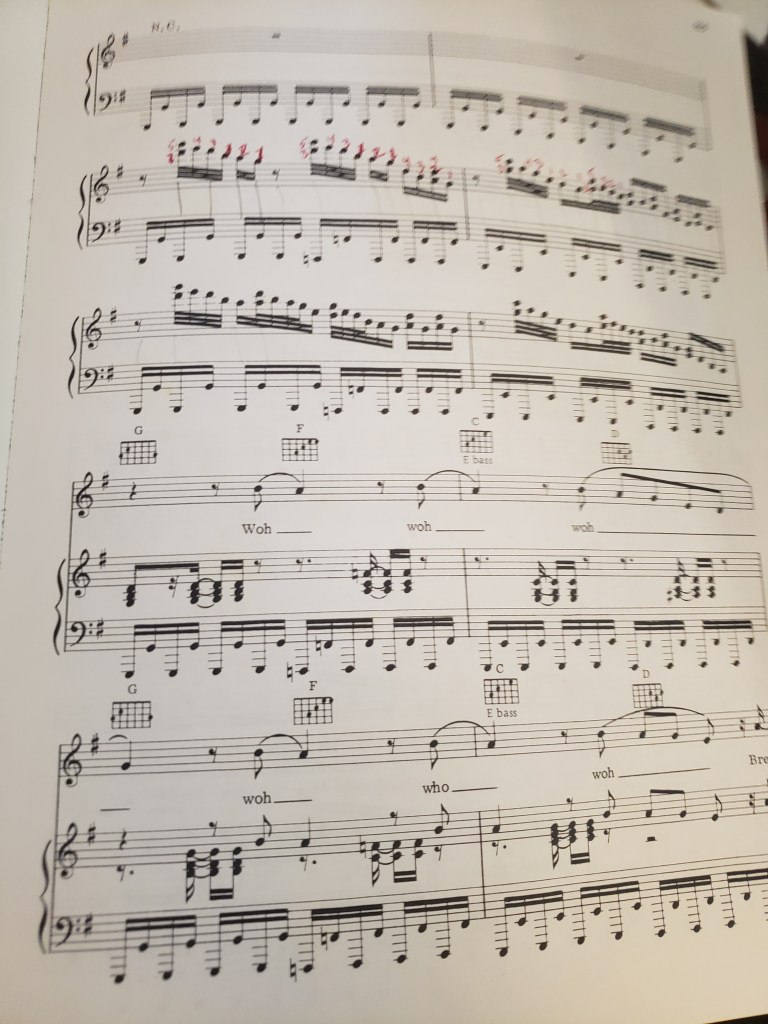

I first encountered this song via sheet music, because I owned the book for Greatest Hits Vol 1 and II. Later, I’d buy The Complete Billy Joel books, which at the time covered everything from Piano Man to Storm Front in album order (and included songs from Cold Spring Harbor in the section devoted to Songs in the Attic). “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant” is in volume one of the two-book collection. My piano teacher, Mrs. Stein, would always let me pick a song to play every week or two in addition to whatever selection from the “course book” I was working through along with my scales and fingering exercises. For years, it was one-off sheet music for popular songs like “November Rain”, but I’d often go back to the Billy Joel books. At the time I got it, I had only heard three albums: An Innocent Man, Greatest Hits Vol. I & II, and Turnstiles. So my selections were mostly songs that were well known alongside tracks from Turnstiles like “Summer Highland Falls” (a song I never really mastered). But I’d often flip through the book to see what other songs were out there, which is how “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant” caught my eye.

How could it not? The title alone suggested something special. What it was and how it sounded, I had no idea, but I’d read through the lyrics look over the music whenever I was flipping through the book. I don’t know why I never decided to just try and play it; I either was worried I wasn’t going to play it right because I’d never heard of it, or that I would get in trouble for playing a song that hadn’t been assigned to me. Yes, that sounds ridiculous, but I have always been ridiculous.

Anyway, I didn’t have to wait too long after buying the sheet music book because I got a stereo for my fifteenth birthday and between my parents and my relatives, received six CDs, one of which was The Stranger (the others were Queen Live and Wembley ’86, Pocket Full of Kryptonite, … And Justice for All, Born to Run, and For Unlawful Carnal Knowlege). I already knew half of the album because those songs were on the Greatest Hits album, and while I can’t say if I went right for “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant” upon my first listen, I know I played it early and often. I think I may have made an attempt at it on the piano before Mrs. Stein assigned it to me, but I didn’t actually start playing it for real until September of 1993 (at least that’s what’s written in the book).

I’ve mentioned this a couple of times on podcasts where I’ve discussed the song or The Stranger as a whole (Fire and Water Records, Long Play), but while the beginning and ending of the song are pretty easy to play, once you get to the beginning of the “Ballad of Brenda and Eddie” section, it becomes a bitch to play. The bass portion of the song, which you play with your left hand is a series of sixteenth notes, all of which are octaves. Now, that’s not hard to do in theory; it’s just that those sixteenth-note octaves go on for at least half the song, finally ending right before the final “bottle of red, bottle of white” lines. I’m neither left-handed nor did I ever master relaxing my wrists enough to have the endurance for those octaves, and that meant that at some point during the Brenda and Eddie verses, my left wrist would not only tense up, it would feel like it was burning. Add to that the way those verses open, where the right hand is playing four measures of what are mostly thirty-second notes before getting to the lyrics. I enjoyed playing the piano and got fairly good at it but despite my efforts, never mastered the song.

That didn’t stop it from becoming one of my favorite Billy Joel songs. I love it for its structure and how that changes throughout to fit the mood (see also: “Bohemian Rhapsody”), but moreover I love what it’s about. In my most recent podcast episode, I talked about his1980s output and I mentioned that while Springsteen wrote for the working class and Mellencamp wrote for the farmers, Billy Joel wrote for the middle-class suburbs. There are a number of songs that show this (the most on the nose being “The Great Suburban Showdown” off Streetlife Serenade), but this is one of the best because it encapsulates a certain feeling of suburban teenhood and is timeless in the way that movies like American Graffiti and Dazed and Confused are despite their very specific settings.

In fact, Brenda and Eddie come from American Graffiti, as they’re described as the “popular steadies and the king of the queen of the prom / ridin’ around with the car top down and the radio on.” I never ran with the Brenda and Eddie crowd, but in a town as small as Sayville, it wasn’t hard to spot the Brenda and Eddies of my high school. I knew the way people looked at the and referred to them, and definitely knew The Diner and how central that was (and to a degree still is) to Long Island culture, to the point where I’ve written stories that have diner scenes.

When Brenda and Eddie decide to get married toward the end of July 1975, Billy notes that “everyone said they were crazy / Brenda, you know that you’re much too lazy / and Eddie could never afford to live that kind of life.” But they go ahead with it anyway and while they find a place to live and buy a waterbed and paintings from Sears, they fight so much that they divorce quickly. It’s a pretty realistic picture and maybe even a caution tale about moving too fast when in love as a teenager (and thankfully, there’s no double suicide like some other stories about movie too fast when in love as a teenager). It’s also, as I realized many, many years after first hearing it, the flip side of a song that came out a decade earlier.

In 1964, Chuck Berry released “You Never Can Tell,” which most of my generation knows from the John Travolta/Uma Thurman dance scene in Pulp Fiction. The song is about two teenagers–Pierre and his girl, who is only referred to as “the Mademoiselle”–who get married as teenagers. In this song, Berry notes that “The old folks wished them well” and come to realize that it’s probably going to work, saying, “‘C’est la vie’ say the old folks / It goes to show you never can tell.”

The second verse is the most important to the context of “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant”:

They furnished off an apartment with a two room roebuck sale

The coolerator was crammed with TV dinners and ginger ale

But when Pierre found work, the little money comin’ worked out well

“C’est la vie” say the old folks

It goes to show you never can tell

Pierre and The Mademoiselle get an apartment and furnish it with things from Sears. Pierre gets a job and the money works out. And the old folks stand corrected because, you know, you never can tell.

As we know, Brenda and Eddie weren’t so lucky.

Maybe it was the optimism of the 1960s versus the harsh realities of the 1970s that are contrasted here; maybe it’s that Chuck Berry wrote upbeat rock and roll and Billy Joel wasn’t afraid to inject melancholy into a happy melody, but he’s telling us that the doubting old folks are probably right and it’s not going to work. But whereas Bruce Springsteen along with Jim Steinman and Meat Loaf would make their teen lovers feel trapped in “The River” and “Paradise by the Dashboard Light”, at least Brenda and Eddie are able to escape and get a second chance, even though they realize that their time as “The King and the Queen” has passed (“but you can never go back there again”).

That’s the most bittersweet moment of the whole song and a moment that I think most of us have had on some level as we’ve grown up and gotten older. I can’t tell you what my particular moment was, although it probably involved me going somewhere I used to go all the time and realizing that I wasn’t the center of anyone’s attention and I was just another customer or face in the crowd. Yes, I know how that sounds, but don’t forget that when you’re a teenager, you are often a walking ego and you often assume that everyone knows what’s going in your life and your world, as if they’ve been watching your movie this entire time. “Nobody cares who you were in high school” is truth because we all reach a point of emotional maturity where we understand that we are, yes, just going through life like everyone else. Some of us do it more quickly than others, and some don’t (read: influencer culture).

The sweetness with which Brenda and Eddie reunite years later is one of my favorite parts of “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant”, and one of the more optimistic parts of the song. Breakups don’t always go smoothly and relationships with exes are often fraught. By the time we’re in the Italian restaurant, they’re no longer “exes” in the sense that you or I would complain about our ex-girlfriends or ex-boyfriends. She’s an “old girlfriend” in the sense that the pain is behind him, and hopefully behind her as well. “Brenda and Eddie” survive in the sense that they can still be close and have something special between one another even though it’s much different than when they were eighteen.

As I get closer to fifty myself, I’ve come to realize how friendships that are fleeting or transient is just another part of life. There are people I was pretty close to in high school and college whom I only see via Instagram or Facebook posts; there are others whom I don’t talk to at all. And then there are the ones who are still there; maybe we take too long to get back to one another and aren’t embedded in one another’s lives like we were in our teens and twenties, but we’re still there and as cheesy as this concluding sentence is going to sound, will always save a seat at a bar, diner, or an Italian restaurant.